For those who are interested in classic touring bicycles that combine speed, maneuverability and comfort, we live in interesting times. Such bicycles have gained in popularity over the past several years, with many custom framebuilders and manufacturers introducing touring models into their line-ups. And while trends like this are not easy to trace, I think it is fair to say that Grant Petersen of Rivendell and Jan Heine of Bicycle Quarterly deserve a great deal of the credit. Rivendell is a small bicycle manufacturer witha distinct philosophy, which they promote with a tireless output of literature. The Bicycle Quarterly (review here) is a niche cycling magazine, with a focus on classic bicycles in the French randonneur tradition.

For those who are interested in classic touring bicycles that combine speed, maneuverability and comfort, we live in interesting times. Such bicycles have gained in popularity over the past several years, with many custom framebuilders and manufacturers introducing touring models into their line-ups. And while trends like this are not easy to trace, I think it is fair to say that Grant Petersen of Rivendell and Jan Heine of Bicycle Quarterly deserve a great deal of the credit. Rivendell is a small bicycle manufacturer witha distinct philosophy, which they promote with a tireless output of literature. The Bicycle Quarterly (review here) is a niche cycling magazine, with a focus on classic bicycles in the French randonneur tradition.To the untrained eye, the type of bicycle promoted by these two camps may seem similar, if not identical: lugged steel frames, wide tires, fenders, racks, classic luggage, leather saddles. But in fact, there are major differences as far as geometry and historical lineage go, and these differences have been inspiring impassioned debates among bicycle connoisseurs for years.

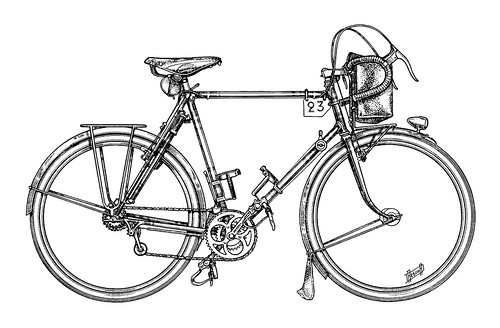

[image via stronglight]

[image via stronglight]When it comes to frame geometry, Rivendell's emphasis is on relaxed angles and clearance for wide tires.Theresulting bicycles are fast, stable, comfortable, and have excellent off-road capacity. The bicyclechampioned by Bicycle Quarterly is rather more specific. Jan Heine believes that bicycles made in the French randonneur tradition - which had reached its height in the 1940s and 50s before its recent resurrection - offer an unrivaled combination of speed and comfort. These bicycles are aggressive and maneuverable, yet cushy and easy to control. They are super light, yet designed to carry a great deal of weight. The main difference from Rivendell structurally, is that such bicycles have what is known as "low trail geometry" while Rivendell bicycles have "mid trail geometry." The difference cannot be easily summed up here, but suffice to say that this factor controls the bicycle's responsiveness, and that mid trail is considered classic whereas low trail is more exotic - not often seen outside the early French tradition. In addition, Jan Heine insists on wide 650B tires, lack of toe overlap, and integrated features such as racks and dynamo lighting. Grant Petersen does not place as much emphasis on 650B tires per se, considers toe overlap to be a non-issue, and does not take lighting into consideration when designing frames.

If these differences seem too subtle for those not familiar with frame design, let me rephrase it like this: The bikes may look similar, but they are built differently and ride differently, and there is some debate about which is "better."

[image via protorio]

[image via protorio]As a reader of both Rivendell literature and Bicycle Quarterly, I am equally convinced by Petersen and Heine; both arguments make sense while I'm reading them. But they can't both be right, because some of their views are in direct opposition!

Since I own a Rivendell and have now ridden close to 2,000 miles on it, it would be fantastic to try a classic randonneur with low trail and 650B wheels for comparison. The problem is that these bicycles are extremely rare. To try one, I would need to either find a vintage Rene Herse or Alex Singer in my size to test ride - which is next to impossible, as they are not exactly the kind of bike a neighbour would have lying around in their garage, or commission a new one custom built just for me by the handful of framebuilders who specialise in them, or find someone who has commissioned such a bike, is the same size as me, and would be willing to lend it to me for a test ride. As neither option is realistic, my interest in classic randonneurs seems destined to remain hypothetical. Has anybody out there actually tried both a Rivendell and a traditionalrandonneur?

We thought it was cute when our cat showed an interest in the Pashley Roadster. But that was nothing compared to her reaction to the vintage Raleigh!

We thought it was cute when our cat showed an interest in the Pashley Roadster. But that was nothing compared to her reaction to the vintage Raleigh! So apparently my cat loves bicycles! -- or at least quality English bicycles? -- We will need to conduct some research to determine the extent of her attraction.

So apparently my cat loves bicycles! -- or at least quality English bicycles? -- We will need to conduct some research to determine the extent of her attraction.

Leaving for Austria again, I bought the new

Leaving for Austria again, I bought the new  In other velo-news I can report from my travels, I saw these neat bicycles during my layover in Frankfurt Airport. These bikes have fenders, dynamo hub lighting, a the double-legged kickstand, a bell, a Basil front basket, a Pletscher rear rack, Schwalbe tires, and what appear to be license plates. From what I could tell, they are for the airport employees and not for flight passengers. Too bad, I would have liked to ride one around the airport!

In other velo-news I can report from my travels, I saw these neat bicycles during my layover in Frankfurt Airport. These bikes have fenders, dynamo hub lighting, a the double-legged kickstand, a bell, a Basil front basket, a Pletscher rear rack, Schwalbe tires, and what appear to be license plates. From what I could tell, they are for the airport employees and not for flight passengers. Too bad, I would have liked to ride one around the airport!

In the comments section of a post from a couple of days ago, I made a remark suggesting that bike shops have financial incentive to sell bikes and accessories separately, as opposed to bikes that do not need additional accessories. I have since received emails asking to expand on that, so let me give it a try.

In the comments section of a post from a couple of days ago, I made a remark suggesting that bike shops have financial incentive to sell bikes and accessories separately, as opposed to bikes that do not need additional accessories. I have since received emails asking to expand on that, so let me give it a try. Consider first, that the retail mark-up on bicycles is usually less, percentage-wise, than the retail mark-up on components and accessories. The better made the bicycle, the more this is so, as production costs for that bike are high and there is a ceiling to what most customers are willing to pay.

Consider first, that the retail mark-up on bicycles is usually less, percentage-wise, than the retail mark-up on components and accessories. The better made the bicycle, the more this is so, as production costs for that bike are high and there is a ceiling to what most customers are willing to pay. So, what incentive is there for bike shops to stock high quality, complete city bicycles and to be motivated to sell them to customers in leu of maximising profits by selling bikes and accessories separately? The way I see it, it is about short-term versus long-term profits - In other words, about building enduring relationships with customers. By acting in a customer's best interest - both in terms of the kind of bicycles they choose to stock in the first place, and in terms of the purchasing suggestions they make to those who walk in off the street - the bike shop is sacrificing immediate profits for the benefits of repeat business and word of mouth advertisement that could result from this customer.

So, what incentive is there for bike shops to stock high quality, complete city bicycles and to be motivated to sell them to customers in leu of maximising profits by selling bikes and accessories separately? The way I see it, it is about short-term versus long-term profits - In other words, about building enduring relationships with customers. By acting in a customer's best interest - both in terms of the kind of bicycles they choose to stock in the first place, and in terms of the purchasing suggestions they make to those who walk in off the street - the bike shop is sacrificing immediate profits for the benefits of repeat business and word of mouth advertisement that could result from this customer.